Genetic sequencing of invertebrates

This page was authored by Willow Neal in 2025.

This page will give a brief description of what happens to our specimens after collection and how we can take an unknown organism and use it’s genes to help us identify it. You can learn more about DNA and genes by looking at the free OpenLearn course “What do genes do”?.

What is genetic barcoding?

After we collect and prepare our specimens, they are ready to send to send to the SANGER institute. Once they arrive, they undergo a process of DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing. This gives us genetic sequence which is then compared to a database to give us an identification. Incredibly, if a whole organism is sent, we can also sometimes see what it was eating as well, because traces of DNA from gut contents can still be detected.

Genetic sequencing is often termed a genetic “barcode”, which is a good way to describe the information that we can derive from animal tissue. A real barcode in the shops is a unique sequence of numbers that identifies the specific item you have picked off the shelf, and the genetic barcode sequence is exactly that; a unique sequence of letters rather than numbers that identifies exactly what species you have.

To identify an organism to the species level (which is the goal, where possible), a known gene is required that is within different organisms. This means that all the invertebrates that we are collecting need to all have the same gene. However, if they all had the same ‘barcode’, this wouldn’t tell us very much and we wouldn’t be able to tell them apart, so this gene also needs to be prone to mutation, so its sequence is unique.

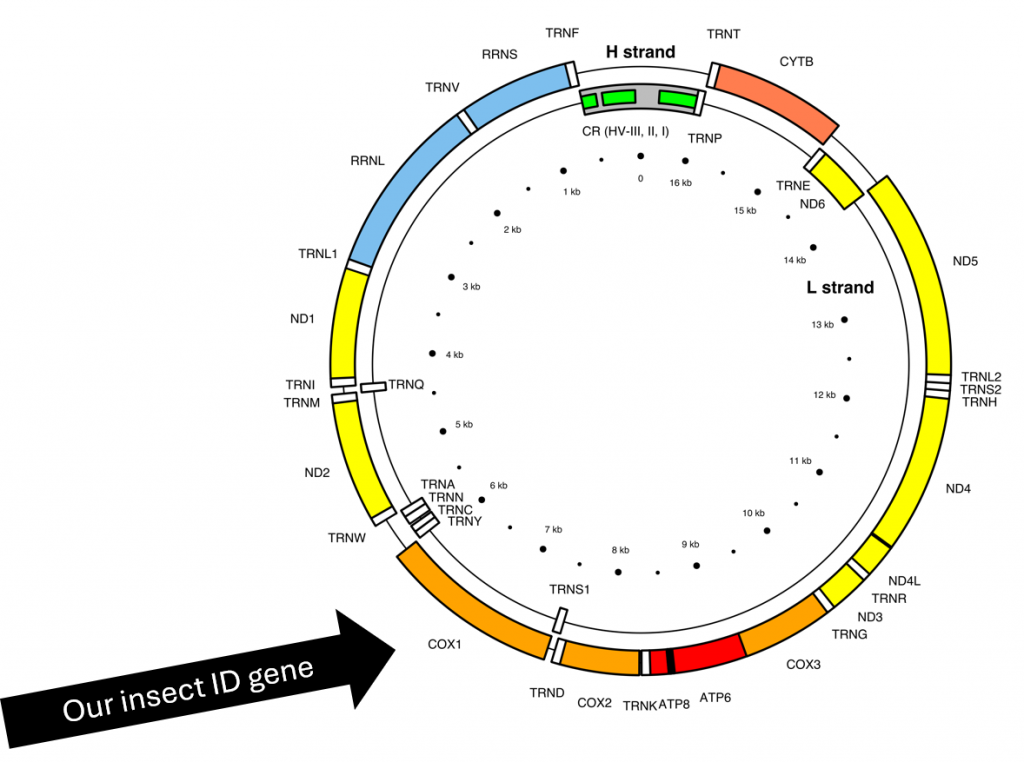

CO-I gene

An ideal candidate gene that is widely used in identifying insect is Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, or more simply CO-I. This gene helps cells convert food into energy and is found in most animals. Because it changes slightly (mutates) between species, it can be used to tell different insects apart.

DNA can be extracted from an entire insect or from a body part, such as a leg, wing, or antenna. To extract the CO-I gene, short, lab-made pieces of DNA called primers are used. Each primer is designed to match one end of the CO-I gene. When added to the sample, they attach to these matching regions and mark the start and end of the gene.

An enzyme called DNA polymerase, which copies DNA, is then added. Because the primers define the boundaries of the CO-I gene, the polymerase copies only that section. This copying happens through repeated cycles of heating and cooling: heating separates the DNA strands, cooling allows the primers to bind, and warming again lets the polymerase build new DNA strands. Each cycle doubles the amount of CO-I DNA. After many cycles, there are millions of identical copies of this gene. This process is called amplification, and it produces enough CO-I DNA to read the sequence accurately for genetic barcoding, which is then compared to a database.

The Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD)

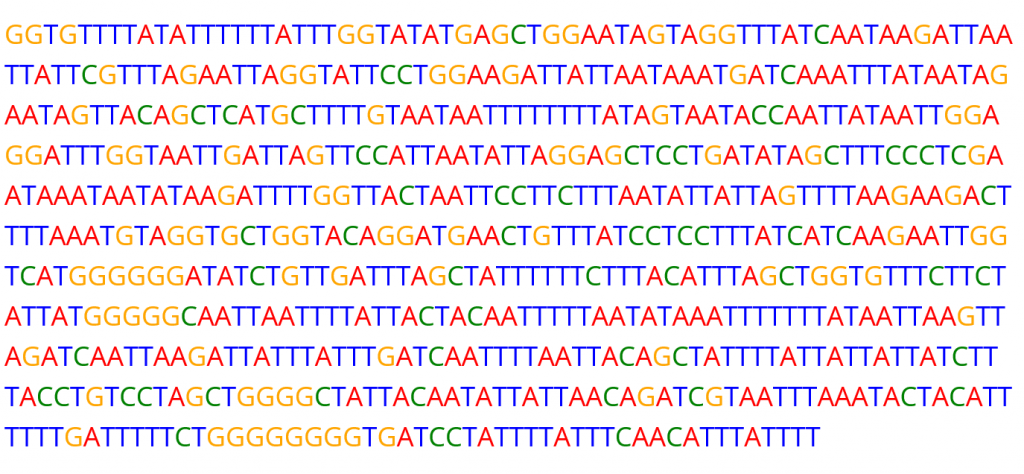

Once the sequence is amplified enough to read, the barcode is produced. The barcode is then compared The Barcode of Life Data Systems’ (BOLD) large database of sequences, which gives us an identification. Below is an example of one of our early collections in 2023, Chorebus avesta, a Braconid wasp that are highly abundant at the OpenLiving Labs which feed upon other insects. You can view the page on this species yourself here.

The long string of letters shown above is the barcode sequence of the CO-I gene. It represents the exact order of the building blocks that make up this gene in our example wasp, Chorebus avesta. The letters A, T, C, and G stand for four chemical bases that make up DNA: adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). DNA is essentially a long chain made from these four components, and the specific order they appear in carries genetic information.

Although many organisms share the same CO-I gene, the exact sequence of A, T, C, and G differs slightly between species. These small differences are what make the sequence useful as a barcode. In this sense, the barcode sequence works much like a product barcode example earlier: it does not describe the organism directly, but it provides a reliable identifier based on a standard region of DNA.

So, while this gives us an ID, it also can tell us about genetic diversity between individuals, which is exceptionally important for health populations of anything– including humans.